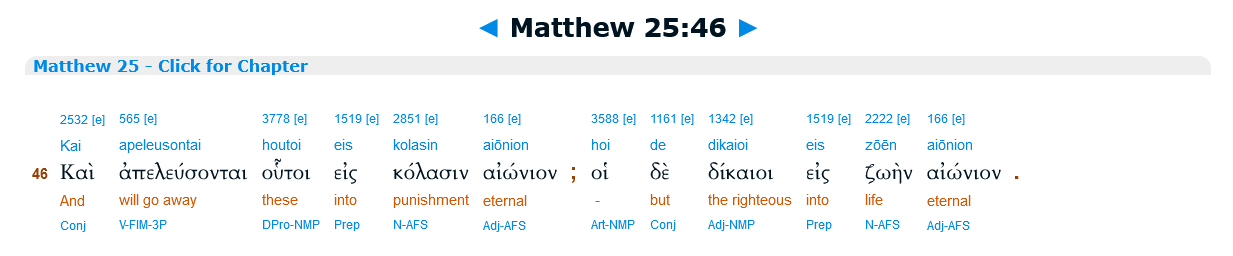

2. “If hell is a temporary state but heaven is a forever state, then why are both denoted by the same word as ‘eternal’?”

Fr. Alvin F. Kimel explains:

The argument seems initially plausible, even compelling, given the parallelism [in Matthew 25:46]; but the inference does not necessarily obtain.

Aiónios is an adjective: it modifies the noun to which it is connected. Adjectives often vary in meaning when the nouns they qualify signify different categories of things, states, or events. When we read the sentence “Jack is a tall man standing in front of a tall building,” we do not jump to the conclusion that Jack is as tall as the building. We recognize the relativity of height with respect to both. When Jesus states that the wicked are sent to

aiónios punishment, we should not assume that it refers to a state of perpetual punishing or that the loss is irretrievable. Jesus is not necessarily threatening interminable suffering.

1

The faulty premise assumed by McClymond here is that the word αἰώνιος always refers to duration—and he seems to think (mistakenly) that universalists grant this premise and only argue that the word can mean “age-long” and thus “temporary” duration. This assumption, that αἰώνιος only ever indicates duration, is a common one, but it is inaccurate nonetheless, as the scholarship of David Konstan and Ilaria Ramelli, for instance, has demonstrated. Adjectivally, αἰώνιος often has a qualitative denotation (“what kind of life and punishment?”), rather than a temporally quantitative denotation (“how long does the life and punishment last?”). Arguably, αἰώνιος in Matthew 25:46 is best understood as indicating that the life and punishment is that “of the coming age,” that is, it is eschatological, otherworldly life and punishment, rather than mere earthly life and punishment. The duration thereof is not necessarily the focus or concern in this text at all.

So, do we then have no basis for believing that “heaven is a forever state”? Much like McClymond, Douglas Potter argues, “If we give up the

everlasting torment of hell, then we must also dismiss the

everlasting happiness of heaven, for the same word is used of both dominions.”

2 This reasoning is fallacious in many ways. First of all, we know the life we have in Christ is eternal not through lexical semantics, but through theological doctrine. That is to say, we know life in Jesus is eternal not because of any one word used to describe it, but because of the nature of that life in Christ by definition. Throughout Scripture we are taught that God (and hence Christ) is immutable, and salvation is understood to be union with this unchanging and ever-faithful redeemer.

Additionally, even if one insists on having a particular word that clearly indicates the permanence of life in Christ, that would not necessarily be αἰώνιος, but rather ἄφθαρτος (“imperishable”) which is used repeatedly in the New Testament to describe salvation in Christ. Analogously speaking, this term indicates that salvation has no ‘expiration date.’ Paul says that our reward is “imperishable” (ἄφθαρτον, 1 Cor. 9:25), that “the dead will be raised imperishable” (ἄφθαρτοι, 1 Cor. 15:52); and keep in mind, this is the same word Paul used to describe God’s own imperishability in Romans 1:23 and 1 Timothy 1:17. Likewise, when Peter intends to emphasize the permanence of our salvific inheritance, he does not use the word αἰώνιος at all, rather he states that we have been granted “an inheritance that is imperishable (ἄφθαρτον), undefiled (ἀμίαντον), and unfading (ἀμάραντον)” (1 Peter 1:4, cf. 1:23, 3:4). Interestingly, these words are never used to describe the punishment or damnation of the lost.

A related question I would pose to infernalists is, if the scope of reconciliation is limited but that of creation is universal, then why are both denoted by the same term ‘all things’ (Col. 1:16-20)? Likewise, if the scope of redemption is limited but that of sin is universal, then why are both denoted by the same term ‘all men’ (Rom. 5:18, cf. 5:19, 11:32, 1 Cor. 15:22)? These universalist texts seem to contain even stronger ‘unbreakable parallels,’ and are much more numerous as well.

[