- Dec 31, 2010

- 5,749

- 2,886

- 113

- Faith

- Christian

- Country

- United States

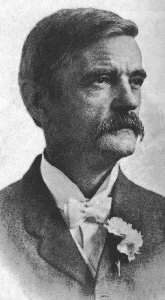

I am currently reading "The Life of George Clark Rankin" located at

George Clark Rankin. The Story of My Life Or More Than a Half Century As I Have Lived It and Seen It Lived Written by Myself at My Own Suggestion and That of Many Others Who Have Known and Loved Me

If you have an Ipad you can join in with me by...

1. Open the above URL in Microsoft IE (won't work in Firefox)

2. Select all and copy (CTL C)

3. Open Microsoft Word and paste (CTR V)

4. Save as a PDF file

5. Download and open Good Reader

6. Copy the PDF file to your Ipad

7. Enjoy the book!

George Clark Ranking was born in 1849 in East Tennessee and became a preacher for the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (which would later form into the UMC). Mr. Rankin would move and spend the rest of his years in Dallas, Texas. A good life! Here are some excerpts from his book...

...Excerpts...

CHAPTER III

An Old-Time Election in East

Tennessee, and Else

In the earlier days, long before the railroads ran through that section, East Tennessee was a country to itself. Its topography made it such. Its people were a peculiar people - rugged, honest and unique. I doubt if their kind was ever known under other circumstances. Hundreds of them were well-to-do, and now and then, in the more fertile communities, there was actual wealth. Especially was this true along the beautiful water-courses where the farm lands are unequaled, even to this good day.

Among them were people of intelligence and high ideals. No country could boast of a finer grade of men and women than lived and flourished in portions of that "Switzerland of America." Their ministers and lawyers and politicians were men of unusual talent. Some of the most eloquent men produced in the United States were born and flourished in East Tennessee.

Those evergreen hills and sun-tipped mountains, covered with a verdant forest in summer and gorgeously decorated with every variety of autumnal hue in the fall and winter; those foaming rivers and leaping cascades; the scream of the eagle by day and the weird hoot of the owl by night - all these natural environments conspired to make men hardy and their speech pictorial and romantic. As a result, there were among them men of native eloquence, veritable sons of thunder in the pulpit, before the bar, and on the hustings.

But far back from these better advantages of soil and institutions of learning, in the gorges, on the hills, along the ravines and amid the mountains, the great throbbing masses of the people were of a different type and belonged almost to another civilization. They were rugged, natural and picturesque. With exceptions, they were not people of books; they did not know the art of letters; they were simple, crude, sincere and physically brave. They enjoyed the freedom of the hills, the shadows of the rocks and the grandeur of the mountains. They were a robust set of men and women, whose dress was mostly homespun, whose muscles were tough, whose countenances were swarthy, and whose rifles were their defense. They took an interest in whatever transpired in their own localities and in the more favored sections of their more fortunate neighbors. They were social, and practiced the law of reciprocity long before Uncle Sam tried to establish it between this country and Canada.

Who among us, having lived in that garden spot of the world, can ever forget the old-fashioned house-raisings, the rough and tumble log-rollings, the frosty corn-shuckings, the road-workings and the quilting-bees?

And when the day's work was over - then the supper - after that the fiddle and the bow, and the old Virginia reel. None but a registered East Tennessean, in his memory, can do justice to experiences like those. No such things ever happened in just that way anywhere on the face of the earth except in that land of the skies.

Therefore, the man who even thinks of those East Tennesseans as sluggards and ignoramuses who got nothing out of life is wide of the mark. They had sense of the horse kind; and they were people of good though crude morals. No such thing as a divorce was known among them. It was rare that one of them ever went to jail in our section; and, if he did, he was disgraced for life.

I never knew, in my boyhood, of but one man going to the penitentiary and it was a shock to the whole country.

---------------------------

It is important to me that... If one is Pentecostal, that one also is Wesleyan in belief. I have met too many Pentecostals who try to get everyone to speak in tongues or try to say that you are not even saved if you don't speak in tongues.

---------------------------------

George Clark Rankin talks of his religious experience in which his first taste of religion was of the Presbyterian sect...

"Grandfather was kind to me and considerate of me, yet he was strict with me. I worked along with him in the field when the weather was agreeable and when it was inclement I helped him in his hatter's shop, for the Civil War was in progress and he had returned at odd times to hatmaking. It was my business in the shop to stretch foxskins and coonskins across a wood-horse and with a knife, made for that purpose, pluck the hair from the fur. I despise the odor of foxskins and coonskins to this good day. He had me to walk two miles every Sunday to Dandridge to Church service and Sunday-school, rain or shine, wet or dry, cold or hot; yet he had fat horses standing in his stable. But he was such a blue-stocking Presbyterian that he never allowed a bridle to go on a horse's head on Sunday. The beasts had to have a day of rest. Old Doctor Minnis was the pastor, and he was the dryest and most interminable preacher I ever heard in my life. He would stand motionless and read his sermons from manuscript for one hour and a half at a time and sometimes longer. Grandfather would sit and never take his eyes off of him, except to glance at me to keep me quiet. It was torture to me." - George Clark Rankin

Then he got it good in the Methodist church in Georgia...

...Quote...

After the team had been fed and we had been to supper we put the mules to the wagon, filled it with chairs and we were off to the meeting. When we reached the locality it was about dark and the people were assembling. Their horses and wagons filled up the cleared spaces and the singing was already in progress. My uncle and his family went well up toward the front, but I dropped into a seat well to the rear. It was an old-fashioned Church, ancient in appearance, oblong in shape and unpretentious. It was situated in a grove about one hundred yards from the road. It was lighted with old tallow-dip candles furnished by the neighbors. It was not a prepossessing-looking place, but it was soon crowded and evidently there was a great deal of interest. A cadaverous-looking man stood up in front with a tuning fork and raised and led the songs. There were a few prayers and the minister came in with his saddlebags and entered the pulpit. He was the Rev. W. H. Heath, the circuit rider. His prayer impressed me with his earnestness and there were many amens to it in the audience. I do not remember his text, but it was a typical revival sermon, full of unction and power.

At its close he invited penitents to the altar and a great many young people flocked to it and bowed for prayer. Many of them became very much affected and they cried out distressingly for mercy. It had a strange effect on me. It made me nervous and I wanted to retire. Directly my uncle came back to me, put his arm around my shoulder and asked me if I did not want to be religious. I told him that I had always had that desire, that mother had brought me up that way, and really I did not know anything else. Then he wanted to know if I had ever professed religion. I hardly understood what he meant and did not answer him. He changed his question and asked me if I had ever been to the altar for prayer, and I answered him in the negative. Then he earnestly besought me to let him take me up to the altar and join the others in being prayed for. It really embarrassed me and I hardly knew what to say to him. He spoke to me of my mother and said that when she was a little girl she went to the altar and that Christ accepted her and she had been a good Christian all these years. That touched me in a tender spot, for mother always did do what was right; and then I was far away from her and wanted to see her. Oh, if she were there to tell me what to do!

By and by I yielded to his entreaty and he led forward to the altar. The minister took me by the hand and spoke tenderly to me as I knelt at the altar. I had gone more out of sympathy than conviction, and I did not know what to do after I bowed there. The others were praying aloud and now and then one would rise shoutingly happy and make the old building ring with his glad praise. It was a novel experience to me. I did not know what to pray for, neither did I know what to expect if I did pray. I spent the most of the hour wondering why I was there and what it all meant. No one explained anything to me. Once in awhile some good old brother or sister would pass my way, strike me on the back and tell me to look up and believe and the blessing would come. But that was not encouraging to me. In fact, it sounded like nonsense and the noise was distracting me. Even in my crude way of thinking I had an idea that religion was a sensible thing and that people ought to become religious intelligently and without all that hurrah. I presume that my ideas were the result of the Presbyterian training given to me by old grandfather. By and by my knees grew tired and the skin was nearly rubbed off my elbows. I thought the service never would close, and when it did conclude with the benediction I heaved a sigh of relief. That was my first experience at the mourner's bench.

As we drove home I did not have much to say, but I listened attentively to the conversation between my uncle and his wife. They were greatly impressed with the meeting, and they spoke first of this one and that one who had "come through" and what a change it would make in the community, as many of them were bad boys. As we were putting up the team my uncle spoke very encouragingly to me; he was delighted with the step I had taken and he pleaded with me not to turn back, but to press on until I found the pearl of great price. He knew my mother would be very happy over the start I had made. Before going to sleep I fell into a train of thought, though I was tired and exhausted. I wondered why I had gone to that altar and what I had gained by it. I felt no special conviction and had received no special impression, but then if my mother had started that way there must be something in it, for she always did what was right. I silently lifted my heart to God in prayer for conviction and guidance. I knew how to pray, for I had come up through prayer, but not the mourner's bench sort. So I determined to continue to attend the meeting and keep on going to the altar until I got religion.

Early the next morning I was up and in a serious frame of mind. I went with the other hands to the cottonfield and at noon I slipped off in the barn and prayed. But the more I thought of the way those young people were moved in the meeting and with what glad hearts they had shouted their praises to God the more it puzzled and confused me. I could not feel the conviction that they had and my heart did not feel melted and tender. I was callous and unmoved in feeling and my distress on account of sin was nothing like theirs. I did not understand my own state of mind and heart. It troubled me, for by this time I really wanted to have an experience like theirs.

When evening came I was ready for Church service and was glad to go. It required no urging. Another large crowd was present and the preacher was as earnest as ever. I did not give much heed to the sermon. In fact, I do not recall a word of it. I was anxious for him to conclude and give me a chance to go to the altar. I had gotten it into my head that there was some real virtue in the mourner's bench; and when the time came I was one of the first to prostrate myself before the altar in prayer. Many others did likewise. Two or three good people at intervals knelt by me and spoke encouragingly to me, but they did not help me. Their talks were mere exhortations to earnestness and faith, but there was no explanation of faith, neither was there any light thrown upon my mind and heart. I wrought myself up into tears and cries for help, but the whole situation was dark and I hardly knew why I cried, or what was the trouble with me. Now and then others would arise from the altar in an ecstasy of joy, but there was no joy for me. When the service closed I was discouraged and felt that maybe I was too hardhearted and the good Spirit could do nothing for me.

After we went home I tossed on the bed before going to sleep and wondered why God did not do for me what he had done for mother and what he was doing in that meeting for those young people at the altar. I could not understand it. But I resolved to keep on trying, and so dropped off to sleep. The next day I had about the same experience and at night saw no change in my condition. And so for several nights I repeated the same distressing experience. The meeting took on such interest that a day service was adopted along with the night exercises, and we attended that also. And one morning while I bowed at the altar in a very disturbed state of mind Brother Tyson, a good local preacher and the father of Rev. J. F. Tyson, now of the Central Conference, sat down by me and, putting his hand on my shoulder, said to me: "Now I want you to sit up awhile and let's talk this matter over quietly. I am sure that you are in earnest, for you have been coming to this altar night after night for several days. I want to ask you a few simple questions." And the following questions were asked and answered:

"My son, do you not love God?"

"I cannot remember when I did not love him."

"Do you believe on his Son, Jesus Christ?"

"I have always believed on Christ. My mother taught me that from my earliest recollection."

"Do you accept him as your Savior?"

"I certainly do, and have always done so."

"Can you think of any sin that is between you and the Savior?"

"No, sir; for I have never committed any bad sins."

"Do you love everybody?"

"Well, I love nearly everybody, but I have no ill-will toward any one. An old man did me a wrong not long ago and I acted ugly toward him, but I do not care to injure him."

"Can you forgive him?"

"Yes, if he wanted me to."

"But, down in your heart, can you wish him well?"

"Yes, sir; I can do that."

"Well, now let me say to you that if you love God, if you accept Jesus Christ as your Savior from sin and if you love your fellowmen and intend by God's help to lead a religious life, that's all there is to religion. In fact, that is all I know about it."

Then he repeated several passages of Scriptures to me proving his assertions. I thought a moment and said to him: "But I do not feel like these young people who have been getting religion night after night. I cannot get happy like them. I do not feel like shouting."

The good man looked at me and smiled and said: "Ah, that's your trouble. You have been trying to feel like them. Now you are not them; you are yourself. You have your own quiet disposition and you are not turned like them. They are excitable and blustery like they are. They give way to their feelings. That's all right, but feeling is not religion. Religion is faith and life. If you have violent feeling with it, all good and well, but if you have faith and not much feeling, why the feeling will take care of itself. To love God and accept Jesus Christ as your Savior, turning away from all sin, and living a godly life, is the substance of true religion."

That was new to me, yet it had been my state of mind from childhood. For I remembered that away back in my early life, when the old preacher held services in my grandmother's house one day and opened the door of the Church, I went forward and gave him my hand. He was to receive me into full membership at the end of six months' probation, but he let it pass out of his mind and failed to attend to it.

As I sat there that morning listening to the earnest exhortation of the good man my tears ceased, my distress left me, light broke in upon my mind, my heart grew joyous, and before I knew just what I was doing I was going all around shaking hands with everybody, and my confusion and darkness disappeared and a great burden rolled off my spirit. I felt exactly like I did when I was a little boy around my mother's knee when she told of Jesus and God and Heaven. It made my heart thrill then, and the same old experience returned to me in that old country Church that beautiful September morning down in old North Georgia.

I at once gave my name to the preacher for membership in the Church, and the following Sunday morning, along with many others, he received me into full membership in the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. It was one of the most delightful days in my recollection. It was the third Sunday in September, 1866, and those Church vows became a living principle in my heart and life. During these forty-five long years, with their alternations of sunshine and shadow, daylight and darkness, success and failure, rejoicing and weeping, fears within and fightings without, I have never ceased to thank God for that autumnal day in the long ago when my name was registered in the Lamb's Book of Life.

.../Quote...

This is the way every Pentecostal should treat the experience. Let everyone get it in their own unique way. Which is John Wesley Methodism in practice.

I did a devotion on RS Sheffey that has over 17,000 views (http://www.christianforums.com/t7630646/). I am finding that the life of GC Rankin closely parallels the life of RS Sheffey.

1. The were both orphaned at an early age

2. They relied upon relatives other than mom and dad to keep them up.

3. They both went to colleges where they would have to work the college farm

4. They were both ordained by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South

5. They both would befriend the local slaves and grieve over their plights.

6. On going to college, they both would have issues with it when it came to doubting their faith.

I am reading, on page 109, about GC Rankin's educational experience, in which he enters the service of a Professor Burkett...

...Quote (Excerpts beginning on page 133)...

Up to this time, as I have already indicated, my faith was simple, confiding and unquestioning. It was the faith of my childhood. Yes, it was the faith of my mother. I did not know the meaning of doubt in my acceptance of Christ and in my belief in the Bible. It had never occurred to me that Christ was not the Son of God and that the Bible was not the exact Word of God. I had never thought how it was possible for Christ to be both God and man, or just how we had received the Bible. My innocent mind was an absolute stranger to quibbles on these matters. Christ was my Savior and I knew him as such from experience; and the Bible was God's truth to guide me through the trials and the duties of this life to a better life beyond the grave. These were accepted as undisputed facts. I had never dreamed that anybody called these truths into question.

But the innocency of my faith received a rude shock just about this time. Professor Burkett had a fine yoke of oxen and with these I did the hauling about the farm. One night they got out and wandered on the railway track and a passing train killed one of them. This broke up his team. He had a son who was a distinguished lawyer, living in Chattanooga, and he owned a fine farm in Meggs County, not far from Decatur. On that farm he kept good stock. So he wrote to the old gentleman that if he would send over to Decatur he would be there at court and he would give him a horse.

I reached Decatur that evening and made myself known to Colonel Burkett. It was a warm evening and after supper they were all sitting in the front yard talking. I was seated near them - an unsophisticated boy. It seems that just before that time, a month or so, a lawyer had left the bar and entered the ministry of the Presbyterian Church. His name was Wallace, and these lawyers were discussing his change from the bar to the pulpit. Some of them seemed to think that he acted wisely, because he was of a very serious turn of mind and too religious to make a successful lawyer. Others thought he had made a mistake and would regret it later on in life.

Then it was that Colonel Burkett assumed to speak. He was a man of strong intellect, well trained and widely read. He was not a religious man. The following is the substance of his deliverance:

"Wallace has not only made a mistake, but he has acted against common sense and reason. There is nothing in religion except tradition on the outside and emotion on the inside. The Bible is not a book to be believed. It is full of discrepancies and contradictions. The Old Testament is horrible. There are things in it that shock decency, to say nothing of a man's sense. The New Testament comes to us by a sort of accident. When King James appointed his commission to collate the manuscripts they threw out some of them and one or two of the present gospels came very nearly being discarded. They were retained by a very narrow majority. A number of the epistles, ascribed to Paul's authorship, were never written by him and they are not entitled to belief. They are a jumble of incongruous writings brought down from an ignorant age, and they are not in keeping with the intelligence of the race. The age has outlived them; they belong to a period filled with ignorance and superstition. Christ, if he ever lived, was a good man, but misguided and died as the result of his fanaticism. Wallace has only written himself down a fool by giving up a good law practice to enter the ministry."

But imagine the effect of all this on my innocent mind. It knocked me into smithereens. I had never dreamed of anything like that I had heard. It aroused all sorts of feelings and all sorts of questionings. It flung me headforemost out into a stormy sea without rudder or compass. The waves grew tumultuous about me. I was almost engulfed.

I arose and went to bed, but I did not go to sleep. I tossed from side to side filled with fear and misgivings. I thought of my mother and her faith; then it occurred to me that mother was just like myself. She had never seen anything of the world, had never read many books and was not an educated woman. She, maybe, was liable to mistakes. The man whom I had heard talk was an educated man; he had informed himself in history; he had traveled; he was a much smarter man than his father, and maybe he knew things that the rest of us did not know. He saw nothing in the Bible to call forth his faith and a number of the others seemed to agree with him. He did not even accept Christ as his Savior. And yet I was starting out to prepare myself to preach this gospel and to hold up Christ to men and women. Is it possible that after all there is nothing in it? Can it be that the whole thing is a fable, as my learned friend had argued? It was one of the most miserable nights I ever spent in my life.

After awhile I went to Professor Burkett and threw open my heart to him. I told him what I had heard in the conversation among those lawyers, but did not tell him that his son was one of the leaders in that tirade against the Bible. I asked him if it were possible that what they said could be true. He began and opened up the whole subject, rehearsed to me the views of skeptics and infidels and then pointed out to me what effect such views had upon life and character. He explained to me how the Bible was inspired, how it had come down through all the ages and how it was believed. Then his deliverance on Christ, and what he had done for the world, was elaborate and convincing. But he said that he had not the time to go over the whole field; that he had a little book that presented the matter in a nutshell, and he reached up and pulled down a small volume and handed it to me. I went to my room and opened the book; it was Watts' Apology for the Bible. It took up every point made by the infidel and answered it succinctly. It gave me the exact history of the King James' translation of the Scriptures and threw a flood of light upon that subject. It gave me some relief, but I still had doubts and fears. I was not inclined to give up my faith, or to go back on the Bible; I was simply fearful and filled with doubts. In whatever direction I would turn they were there to afflict me and to hinder me.

I was fighting a severe battle and victory was nowhere in sight. My faith remained intact, but it was clouded; my hope was still anchored, but the wild winds and the stormy waves were belaboring me. I was struggling to find a landing away from the fury of the storm; I was striving to quell the ebullition of my mental fermentation - yea, I was flinging my shoulders with might and main against the formidable obstructions that were blocking my progress.

I learned long afterward that I was only passing through that crisis of doubt that comes to the experience of every honest inquirer after the truth; yes, I had reached the point at which the innocence of faith had its severest trial - the time when the mind cries out after a more solid ground of hope than that accepted in childhood; a foundation that is not only built upon Christ, but that furnished a rational reason for the hope that is within the bosom.

In the meantime I clung to my faith and followed in the glimmering light of my hope. With all my disturbance and oftimes anguish of spirit I tenaciously held on to the Bible and conscientiously gripped the hand of my Savior. I lost the innocence of my faith, but acquired a broader and a more rational trust; I saw the brilliancy of my childhood hope take on a faded hue, but I anchored my desire in the haven of rest and my expectation rose to sublimer heights as I emerged from the gloom and looked out upon the expanse of an unfolding future.

As the years passed by and my mind became more matured my reasoning, faculties grew stronger, my intellectual horizon lifted its boundary circle and became more extended in its scope, and I found myself able to digest more nourishing meats and to cope with deeper and more perplexing problems.

In other words, I ceased to be a child in my faith and became a full-grown man in my knowledge of God and his methods of revealing his will to humanity. But the result came to me at the end of a long struggle that tried the joints in my harness, and that gave me careful investigation into the elements that entered into the foundation of my faith and hope. Therefore it has been many a long day since troublesome doubts harassed and disturbed the state of my mind. It was a fortunate coincidence that, along with those first struggles, I had a strong and steady hand to lead me and a wise and settled mind to help me solve the problems. In addition to this the thought of my mother's prayers for me and the influence of her godly tuition helped to strengthen and sustain me.

Now comes the sequel to this story, which will require me to skip over several years and give another incident closely related to it. I was pastor of a city Church, in which city the State University was located. By the student body I was elected to preach the annual sermon before the Young Men's Christian Association of the institution. They chose my subject for me - "The Inspiration and Authenticity of the Scriptures". I had three months in which to make the preparation and I devoted much time to reading and research on the question.

I had an immense audience, not only of students, but of local people and the faculty. I had liberty in its delivery, and such was the appreciation of it by the University authorities that they gave me the degree of Doctor of Divinity. This was unmerited and not deserved, but I was not responsible for their action. The sermon was published by request in the daily papers of the city and given a wide reading. I received many letters of appreciation from divers friends, and one of them was from Colonel Burkett. He did not know me. But I knew him. I will repeat a few of the passages in that letter:

"I have read with interest your sermon on the 'Divine Inspiration and Authenticity of the Scriptures', as published in the daily press, and I write this apprecition of it for two reasons. In the first place, I have gotten profit out of it. It has given me light on the subject. I have read a great deal on that question and have my peculiar views about it, but your treatment of it has inclined me to re-examine my premises and arguments and see if my conclusions are altogether sound. I was brought up under religious tuition and my predilections favor the Bible story; but my reason, in my more matured manhood, rebelled against its validity. This has been my position for years. But I must confess I get no pleasure out of my doubts and infidelity. I really want to believe the Bible and to have faith in a Savior. As far as my observations go the Christian man is the happiest and the most useful of all men. My heart wants to be a Christian, but my head will not give its consent. But I am determined to make further inquiry into this matter.

"In the second place, a friend of mine who knows you tells me that you are a former student of my father, and this fact quickens my interest in you and in the sermon. As I re-read it I felt that it was my father preaching through you. He has long since been gone, but I revere his memory and appreciate his work. Since he was instrumental in helping to produce you I am proud of you for his sake. My father was not a faultless man, but he had a generous heart and a confiding faith, and his work survives him in the poor boys whom he helped to get an education. He lived to a good purpose and spent his long life in helping others. His sacrifices were many, but were he living his reward would be ample in the thought that he had aided others to make the world better."

When I read that letter it occurred to me that Colonel Burkett had unwittingly made that sermon possible. Had I not sat there as an innocent youth on that September evening in the long ago and heard his attacks upon the Bible and his doubts concerning Christ, I perhaps would never have gone into so full an investigation of that subject and preached that discourse. The experience cost me an anguish that words can never express, but out of it have come some of the most valuable lessons of my ministry. It has caused me to have more sympathy with that class of men who seem to want to know the truth, but whose perverseness leads them to either doubt and discard it or to treat it with indifference and let it go by default. My observation is that men get no comfort out of their skepticism and infidelity; that down in their hearts, in their better moments, they want to accept the truth and be Christians.

.../quote...

George Clark Rankin. The Story of My Life Or More Than a Half Century As I Have Lived It and Seen It Lived Written by Myself at My Own Suggestion and That of Many Others Who Have Known and Loved Me

If you have an Ipad you can join in with me by...

1. Open the above URL in Microsoft IE (won't work in Firefox)

2. Select all and copy (CTL C)

3. Open Microsoft Word and paste (CTR V)

4. Save as a PDF file

5. Download and open Good Reader

6. Copy the PDF file to your Ipad

7. Enjoy the book!

George Clark Ranking was born in 1849 in East Tennessee and became a preacher for the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (which would later form into the UMC). Mr. Rankin would move and spend the rest of his years in Dallas, Texas. A good life! Here are some excerpts from his book...

...Excerpts...

CHAPTER III

An Old-Time Election in East

Tennessee, and Else

In the earlier days, long before the railroads ran through that section, East Tennessee was a country to itself. Its topography made it such. Its people were a peculiar people - rugged, honest and unique. I doubt if their kind was ever known under other circumstances. Hundreds of them were well-to-do, and now and then, in the more fertile communities, there was actual wealth. Especially was this true along the beautiful water-courses where the farm lands are unequaled, even to this good day.

Among them were people of intelligence and high ideals. No country could boast of a finer grade of men and women than lived and flourished in portions of that "Switzerland of America." Their ministers and lawyers and politicians were men of unusual talent. Some of the most eloquent men produced in the United States were born and flourished in East Tennessee.

Those evergreen hills and sun-tipped mountains, covered with a verdant forest in summer and gorgeously decorated with every variety of autumnal hue in the fall and winter; those foaming rivers and leaping cascades; the scream of the eagle by day and the weird hoot of the owl by night - all these natural environments conspired to make men hardy and their speech pictorial and romantic. As a result, there were among them men of native eloquence, veritable sons of thunder in the pulpit, before the bar, and on the hustings.

But far back from these better advantages of soil and institutions of learning, in the gorges, on the hills, along the ravines and amid the mountains, the great throbbing masses of the people were of a different type and belonged almost to another civilization. They were rugged, natural and picturesque. With exceptions, they were not people of books; they did not know the art of letters; they were simple, crude, sincere and physically brave. They enjoyed the freedom of the hills, the shadows of the rocks and the grandeur of the mountains. They were a robust set of men and women, whose dress was mostly homespun, whose muscles were tough, whose countenances were swarthy, and whose rifles were their defense. They took an interest in whatever transpired in their own localities and in the more favored sections of their more fortunate neighbors. They were social, and practiced the law of reciprocity long before Uncle Sam tried to establish it between this country and Canada.

Who among us, having lived in that garden spot of the world, can ever forget the old-fashioned house-raisings, the rough and tumble log-rollings, the frosty corn-shuckings, the road-workings and the quilting-bees?

And when the day's work was over - then the supper - after that the fiddle and the bow, and the old Virginia reel. None but a registered East Tennessean, in his memory, can do justice to experiences like those. No such things ever happened in just that way anywhere on the face of the earth except in that land of the skies.

Therefore, the man who even thinks of those East Tennesseans as sluggards and ignoramuses who got nothing out of life is wide of the mark. They had sense of the horse kind; and they were people of good though crude morals. No such thing as a divorce was known among them. It was rare that one of them ever went to jail in our section; and, if he did, he was disgraced for life.

I never knew, in my boyhood, of but one man going to the penitentiary and it was a shock to the whole country.

---------------------------

It is important to me that... If one is Pentecostal, that one also is Wesleyan in belief. I have met too many Pentecostals who try to get everyone to speak in tongues or try to say that you are not even saved if you don't speak in tongues.

---------------------------------

George Clark Rankin talks of his religious experience in which his first taste of religion was of the Presbyterian sect...

"Grandfather was kind to me and considerate of me, yet he was strict with me. I worked along with him in the field when the weather was agreeable and when it was inclement I helped him in his hatter's shop, for the Civil War was in progress and he had returned at odd times to hatmaking. It was my business in the shop to stretch foxskins and coonskins across a wood-horse and with a knife, made for that purpose, pluck the hair from the fur. I despise the odor of foxskins and coonskins to this good day. He had me to walk two miles every Sunday to Dandridge to Church service and Sunday-school, rain or shine, wet or dry, cold or hot; yet he had fat horses standing in his stable. But he was such a blue-stocking Presbyterian that he never allowed a bridle to go on a horse's head on Sunday. The beasts had to have a day of rest. Old Doctor Minnis was the pastor, and he was the dryest and most interminable preacher I ever heard in my life. He would stand motionless and read his sermons from manuscript for one hour and a half at a time and sometimes longer. Grandfather would sit and never take his eyes off of him, except to glance at me to keep me quiet. It was torture to me." - George Clark Rankin

Then he got it good in the Methodist church in Georgia...

...Quote...

After the team had been fed and we had been to supper we put the mules to the wagon, filled it with chairs and we were off to the meeting. When we reached the locality it was about dark and the people were assembling. Their horses and wagons filled up the cleared spaces and the singing was already in progress. My uncle and his family went well up toward the front, but I dropped into a seat well to the rear. It was an old-fashioned Church, ancient in appearance, oblong in shape and unpretentious. It was situated in a grove about one hundred yards from the road. It was lighted with old tallow-dip candles furnished by the neighbors. It was not a prepossessing-looking place, but it was soon crowded and evidently there was a great deal of interest. A cadaverous-looking man stood up in front with a tuning fork and raised and led the songs. There were a few prayers and the minister came in with his saddlebags and entered the pulpit. He was the Rev. W. H. Heath, the circuit rider. His prayer impressed me with his earnestness and there were many amens to it in the audience. I do not remember his text, but it was a typical revival sermon, full of unction and power.

At its close he invited penitents to the altar and a great many young people flocked to it and bowed for prayer. Many of them became very much affected and they cried out distressingly for mercy. It had a strange effect on me. It made me nervous and I wanted to retire. Directly my uncle came back to me, put his arm around my shoulder and asked me if I did not want to be religious. I told him that I had always had that desire, that mother had brought me up that way, and really I did not know anything else. Then he wanted to know if I had ever professed religion. I hardly understood what he meant and did not answer him. He changed his question and asked me if I had ever been to the altar for prayer, and I answered him in the negative. Then he earnestly besought me to let him take me up to the altar and join the others in being prayed for. It really embarrassed me and I hardly knew what to say to him. He spoke to me of my mother and said that when she was a little girl she went to the altar and that Christ accepted her and she had been a good Christian all these years. That touched me in a tender spot, for mother always did do what was right; and then I was far away from her and wanted to see her. Oh, if she were there to tell me what to do!

By and by I yielded to his entreaty and he led forward to the altar. The minister took me by the hand and spoke tenderly to me as I knelt at the altar. I had gone more out of sympathy than conviction, and I did not know what to do after I bowed there. The others were praying aloud and now and then one would rise shoutingly happy and make the old building ring with his glad praise. It was a novel experience to me. I did not know what to pray for, neither did I know what to expect if I did pray. I spent the most of the hour wondering why I was there and what it all meant. No one explained anything to me. Once in awhile some good old brother or sister would pass my way, strike me on the back and tell me to look up and believe and the blessing would come. But that was not encouraging to me. In fact, it sounded like nonsense and the noise was distracting me. Even in my crude way of thinking I had an idea that religion was a sensible thing and that people ought to become religious intelligently and without all that hurrah. I presume that my ideas were the result of the Presbyterian training given to me by old grandfather. By and by my knees grew tired and the skin was nearly rubbed off my elbows. I thought the service never would close, and when it did conclude with the benediction I heaved a sigh of relief. That was my first experience at the mourner's bench.

As we drove home I did not have much to say, but I listened attentively to the conversation between my uncle and his wife. They were greatly impressed with the meeting, and they spoke first of this one and that one who had "come through" and what a change it would make in the community, as many of them were bad boys. As we were putting up the team my uncle spoke very encouragingly to me; he was delighted with the step I had taken and he pleaded with me not to turn back, but to press on until I found the pearl of great price. He knew my mother would be very happy over the start I had made. Before going to sleep I fell into a train of thought, though I was tired and exhausted. I wondered why I had gone to that altar and what I had gained by it. I felt no special conviction and had received no special impression, but then if my mother had started that way there must be something in it, for she always did what was right. I silently lifted my heart to God in prayer for conviction and guidance. I knew how to pray, for I had come up through prayer, but not the mourner's bench sort. So I determined to continue to attend the meeting and keep on going to the altar until I got religion.

Early the next morning I was up and in a serious frame of mind. I went with the other hands to the cottonfield and at noon I slipped off in the barn and prayed. But the more I thought of the way those young people were moved in the meeting and with what glad hearts they had shouted their praises to God the more it puzzled and confused me. I could not feel the conviction that they had and my heart did not feel melted and tender. I was callous and unmoved in feeling and my distress on account of sin was nothing like theirs. I did not understand my own state of mind and heart. It troubled me, for by this time I really wanted to have an experience like theirs.

When evening came I was ready for Church service and was glad to go. It required no urging. Another large crowd was present and the preacher was as earnest as ever. I did not give much heed to the sermon. In fact, I do not recall a word of it. I was anxious for him to conclude and give me a chance to go to the altar. I had gotten it into my head that there was some real virtue in the mourner's bench; and when the time came I was one of the first to prostrate myself before the altar in prayer. Many others did likewise. Two or three good people at intervals knelt by me and spoke encouragingly to me, but they did not help me. Their talks were mere exhortations to earnestness and faith, but there was no explanation of faith, neither was there any light thrown upon my mind and heart. I wrought myself up into tears and cries for help, but the whole situation was dark and I hardly knew why I cried, or what was the trouble with me. Now and then others would arise from the altar in an ecstasy of joy, but there was no joy for me. When the service closed I was discouraged and felt that maybe I was too hardhearted and the good Spirit could do nothing for me.

After we went home I tossed on the bed before going to sleep and wondered why God did not do for me what he had done for mother and what he was doing in that meeting for those young people at the altar. I could not understand it. But I resolved to keep on trying, and so dropped off to sleep. The next day I had about the same experience and at night saw no change in my condition. And so for several nights I repeated the same distressing experience. The meeting took on such interest that a day service was adopted along with the night exercises, and we attended that also. And one morning while I bowed at the altar in a very disturbed state of mind Brother Tyson, a good local preacher and the father of Rev. J. F. Tyson, now of the Central Conference, sat down by me and, putting his hand on my shoulder, said to me: "Now I want you to sit up awhile and let's talk this matter over quietly. I am sure that you are in earnest, for you have been coming to this altar night after night for several days. I want to ask you a few simple questions." And the following questions were asked and answered:

"My son, do you not love God?"

"I cannot remember when I did not love him."

"Do you believe on his Son, Jesus Christ?"

"I have always believed on Christ. My mother taught me that from my earliest recollection."

"Do you accept him as your Savior?"

"I certainly do, and have always done so."

"Can you think of any sin that is between you and the Savior?"

"No, sir; for I have never committed any bad sins."

"Do you love everybody?"

"Well, I love nearly everybody, but I have no ill-will toward any one. An old man did me a wrong not long ago and I acted ugly toward him, but I do not care to injure him."

"Can you forgive him?"

"Yes, if he wanted me to."

"But, down in your heart, can you wish him well?"

"Yes, sir; I can do that."

"Well, now let me say to you that if you love God, if you accept Jesus Christ as your Savior from sin and if you love your fellowmen and intend by God's help to lead a religious life, that's all there is to religion. In fact, that is all I know about it."

Then he repeated several passages of Scriptures to me proving his assertions. I thought a moment and said to him: "But I do not feel like these young people who have been getting religion night after night. I cannot get happy like them. I do not feel like shouting."

The good man looked at me and smiled and said: "Ah, that's your trouble. You have been trying to feel like them. Now you are not them; you are yourself. You have your own quiet disposition and you are not turned like them. They are excitable and blustery like they are. They give way to their feelings. That's all right, but feeling is not religion. Religion is faith and life. If you have violent feeling with it, all good and well, but if you have faith and not much feeling, why the feeling will take care of itself. To love God and accept Jesus Christ as your Savior, turning away from all sin, and living a godly life, is the substance of true religion."

That was new to me, yet it had been my state of mind from childhood. For I remembered that away back in my early life, when the old preacher held services in my grandmother's house one day and opened the door of the Church, I went forward and gave him my hand. He was to receive me into full membership at the end of six months' probation, but he let it pass out of his mind and failed to attend to it.

As I sat there that morning listening to the earnest exhortation of the good man my tears ceased, my distress left me, light broke in upon my mind, my heart grew joyous, and before I knew just what I was doing I was going all around shaking hands with everybody, and my confusion and darkness disappeared and a great burden rolled off my spirit. I felt exactly like I did when I was a little boy around my mother's knee when she told of Jesus and God and Heaven. It made my heart thrill then, and the same old experience returned to me in that old country Church that beautiful September morning down in old North Georgia.

I at once gave my name to the preacher for membership in the Church, and the following Sunday morning, along with many others, he received me into full membership in the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. It was one of the most delightful days in my recollection. It was the third Sunday in September, 1866, and those Church vows became a living principle in my heart and life. During these forty-five long years, with their alternations of sunshine and shadow, daylight and darkness, success and failure, rejoicing and weeping, fears within and fightings without, I have never ceased to thank God for that autumnal day in the long ago when my name was registered in the Lamb's Book of Life.

.../Quote...

This is the way every Pentecostal should treat the experience. Let everyone get it in their own unique way. Which is John Wesley Methodism in practice.

I did a devotion on RS Sheffey that has over 17,000 views (http://www.christianforums.com/t7630646/). I am finding that the life of GC Rankin closely parallels the life of RS Sheffey.

1. The were both orphaned at an early age

2. They relied upon relatives other than mom and dad to keep them up.

3. They both went to colleges where they would have to work the college farm

4. They were both ordained by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South

5. They both would befriend the local slaves and grieve over their plights.

6. On going to college, they both would have issues with it when it came to doubting their faith.

I am reading, on page 109, about GC Rankin's educational experience, in which he enters the service of a Professor Burkett...

...Quote (Excerpts beginning on page 133)...

Up to this time, as I have already indicated, my faith was simple, confiding and unquestioning. It was the faith of my childhood. Yes, it was the faith of my mother. I did not know the meaning of doubt in my acceptance of Christ and in my belief in the Bible. It had never occurred to me that Christ was not the Son of God and that the Bible was not the exact Word of God. I had never thought how it was possible for Christ to be both God and man, or just how we had received the Bible. My innocent mind was an absolute stranger to quibbles on these matters. Christ was my Savior and I knew him as such from experience; and the Bible was God's truth to guide me through the trials and the duties of this life to a better life beyond the grave. These were accepted as undisputed facts. I had never dreamed that anybody called these truths into question.

But the innocency of my faith received a rude shock just about this time. Professor Burkett had a fine yoke of oxen and with these I did the hauling about the farm. One night they got out and wandered on the railway track and a passing train killed one of them. This broke up his team. He had a son who was a distinguished lawyer, living in Chattanooga, and he owned a fine farm in Meggs County, not far from Decatur. On that farm he kept good stock. So he wrote to the old gentleman that if he would send over to Decatur he would be there at court and he would give him a horse.

I reached Decatur that evening and made myself known to Colonel Burkett. It was a warm evening and after supper they were all sitting in the front yard talking. I was seated near them - an unsophisticated boy. It seems that just before that time, a month or so, a lawyer had left the bar and entered the ministry of the Presbyterian Church. His name was Wallace, and these lawyers were discussing his change from the bar to the pulpit. Some of them seemed to think that he acted wisely, because he was of a very serious turn of mind and too religious to make a successful lawyer. Others thought he had made a mistake and would regret it later on in life.

Then it was that Colonel Burkett assumed to speak. He was a man of strong intellect, well trained and widely read. He was not a religious man. The following is the substance of his deliverance:

"Wallace has not only made a mistake, but he has acted against common sense and reason. There is nothing in religion except tradition on the outside and emotion on the inside. The Bible is not a book to be believed. It is full of discrepancies and contradictions. The Old Testament is horrible. There are things in it that shock decency, to say nothing of a man's sense. The New Testament comes to us by a sort of accident. When King James appointed his commission to collate the manuscripts they threw out some of them and one or two of the present gospels came very nearly being discarded. They were retained by a very narrow majority. A number of the epistles, ascribed to Paul's authorship, were never written by him and they are not entitled to belief. They are a jumble of incongruous writings brought down from an ignorant age, and they are not in keeping with the intelligence of the race. The age has outlived them; they belong to a period filled with ignorance and superstition. Christ, if he ever lived, was a good man, but misguided and died as the result of his fanaticism. Wallace has only written himself down a fool by giving up a good law practice to enter the ministry."

But imagine the effect of all this on my innocent mind. It knocked me into smithereens. I had never dreamed of anything like that I had heard. It aroused all sorts of feelings and all sorts of questionings. It flung me headforemost out into a stormy sea without rudder or compass. The waves grew tumultuous about me. I was almost engulfed.

I arose and went to bed, but I did not go to sleep. I tossed from side to side filled with fear and misgivings. I thought of my mother and her faith; then it occurred to me that mother was just like myself. She had never seen anything of the world, had never read many books and was not an educated woman. She, maybe, was liable to mistakes. The man whom I had heard talk was an educated man; he had informed himself in history; he had traveled; he was a much smarter man than his father, and maybe he knew things that the rest of us did not know. He saw nothing in the Bible to call forth his faith and a number of the others seemed to agree with him. He did not even accept Christ as his Savior. And yet I was starting out to prepare myself to preach this gospel and to hold up Christ to men and women. Is it possible that after all there is nothing in it? Can it be that the whole thing is a fable, as my learned friend had argued? It was one of the most miserable nights I ever spent in my life.

After awhile I went to Professor Burkett and threw open my heart to him. I told him what I had heard in the conversation among those lawyers, but did not tell him that his son was one of the leaders in that tirade against the Bible. I asked him if it were possible that what they said could be true. He began and opened up the whole subject, rehearsed to me the views of skeptics and infidels and then pointed out to me what effect such views had upon life and character. He explained to me how the Bible was inspired, how it had come down through all the ages and how it was believed. Then his deliverance on Christ, and what he had done for the world, was elaborate and convincing. But he said that he had not the time to go over the whole field; that he had a little book that presented the matter in a nutshell, and he reached up and pulled down a small volume and handed it to me. I went to my room and opened the book; it was Watts' Apology for the Bible. It took up every point made by the infidel and answered it succinctly. It gave me the exact history of the King James' translation of the Scriptures and threw a flood of light upon that subject. It gave me some relief, but I still had doubts and fears. I was not inclined to give up my faith, or to go back on the Bible; I was simply fearful and filled with doubts. In whatever direction I would turn they were there to afflict me and to hinder me.

I was fighting a severe battle and victory was nowhere in sight. My faith remained intact, but it was clouded; my hope was still anchored, but the wild winds and the stormy waves were belaboring me. I was struggling to find a landing away from the fury of the storm; I was striving to quell the ebullition of my mental fermentation - yea, I was flinging my shoulders with might and main against the formidable obstructions that were blocking my progress.

I learned long afterward that I was only passing through that crisis of doubt that comes to the experience of every honest inquirer after the truth; yes, I had reached the point at which the innocence of faith had its severest trial - the time when the mind cries out after a more solid ground of hope than that accepted in childhood; a foundation that is not only built upon Christ, but that furnished a rational reason for the hope that is within the bosom.

In the meantime I clung to my faith and followed in the glimmering light of my hope. With all my disturbance and oftimes anguish of spirit I tenaciously held on to the Bible and conscientiously gripped the hand of my Savior. I lost the innocence of my faith, but acquired a broader and a more rational trust; I saw the brilliancy of my childhood hope take on a faded hue, but I anchored my desire in the haven of rest and my expectation rose to sublimer heights as I emerged from the gloom and looked out upon the expanse of an unfolding future.

As the years passed by and my mind became more matured my reasoning, faculties grew stronger, my intellectual horizon lifted its boundary circle and became more extended in its scope, and I found myself able to digest more nourishing meats and to cope with deeper and more perplexing problems.

In other words, I ceased to be a child in my faith and became a full-grown man in my knowledge of God and his methods of revealing his will to humanity. But the result came to me at the end of a long struggle that tried the joints in my harness, and that gave me careful investigation into the elements that entered into the foundation of my faith and hope. Therefore it has been many a long day since troublesome doubts harassed and disturbed the state of my mind. It was a fortunate coincidence that, along with those first struggles, I had a strong and steady hand to lead me and a wise and settled mind to help me solve the problems. In addition to this the thought of my mother's prayers for me and the influence of her godly tuition helped to strengthen and sustain me.

Now comes the sequel to this story, which will require me to skip over several years and give another incident closely related to it. I was pastor of a city Church, in which city the State University was located. By the student body I was elected to preach the annual sermon before the Young Men's Christian Association of the institution. They chose my subject for me - "The Inspiration and Authenticity of the Scriptures". I had three months in which to make the preparation and I devoted much time to reading and research on the question.

I had an immense audience, not only of students, but of local people and the faculty. I had liberty in its delivery, and such was the appreciation of it by the University authorities that they gave me the degree of Doctor of Divinity. This was unmerited and not deserved, but I was not responsible for their action. The sermon was published by request in the daily papers of the city and given a wide reading. I received many letters of appreciation from divers friends, and one of them was from Colonel Burkett. He did not know me. But I knew him. I will repeat a few of the passages in that letter:

"I have read with interest your sermon on the 'Divine Inspiration and Authenticity of the Scriptures', as published in the daily press, and I write this apprecition of it for two reasons. In the first place, I have gotten profit out of it. It has given me light on the subject. I have read a great deal on that question and have my peculiar views about it, but your treatment of it has inclined me to re-examine my premises and arguments and see if my conclusions are altogether sound. I was brought up under religious tuition and my predilections favor the Bible story; but my reason, in my more matured manhood, rebelled against its validity. This has been my position for years. But I must confess I get no pleasure out of my doubts and infidelity. I really want to believe the Bible and to have faith in a Savior. As far as my observations go the Christian man is the happiest and the most useful of all men. My heart wants to be a Christian, but my head will not give its consent. But I am determined to make further inquiry into this matter.

"In the second place, a friend of mine who knows you tells me that you are a former student of my father, and this fact quickens my interest in you and in the sermon. As I re-read it I felt that it was my father preaching through you. He has long since been gone, but I revere his memory and appreciate his work. Since he was instrumental in helping to produce you I am proud of you for his sake. My father was not a faultless man, but he had a generous heart and a confiding faith, and his work survives him in the poor boys whom he helped to get an education. He lived to a good purpose and spent his long life in helping others. His sacrifices were many, but were he living his reward would be ample in the thought that he had aided others to make the world better."

When I read that letter it occurred to me that Colonel Burkett had unwittingly made that sermon possible. Had I not sat there as an innocent youth on that September evening in the long ago and heard his attacks upon the Bible and his doubts concerning Christ, I perhaps would never have gone into so full an investigation of that subject and preached that discourse. The experience cost me an anguish that words can never express, but out of it have come some of the most valuable lessons of my ministry. It has caused me to have more sympathy with that class of men who seem to want to know the truth, but whose perverseness leads them to either doubt and discard it or to treat it with indifference and let it go by default. My observation is that men get no comfort out of their skepticism and infidelity; that down in their hearts, in their better moments, they want to accept the truth and be Christians.

.../quote...