The Learner

Well-Known Member

Anarthrous Predicate Nominatives preceding the verb where a definite interpretation seems the

most likely possibility:

Matthew 5:34, θρόνος ἐστὶν τοῦ θεοῦ (“it is the throne of God”) – There is only one throne of God.

Matthew 5:35, μήτε εἰς Ἱεροσόλυμα, ὅτι πόλις ἐστὶν τοῦ μεγάλου βασιλέως (“nor by Jerusalem, because it is the city of the Great King”) – There is only one Jerusalem, one city of the great King.

Matthew 12:50, αὐτός μου ἀδελφὸς καὶ ἀδελφὴ καὶ μήτηρ ἐστίν (“he is the brother of me and the sister of me and the mother of me”) – By comparison with v.48 where brother, sister and mother have the article, it is evident that these terms are definite here as well.

Matthew 13:39b, ὁ δὲ θερισμὸς συντέλεια αἰῶνός ἐστιν (“and the harvest is the end of the age”)

Matthew 14:33, ἀληθῶς θεοῦ υἱὸς εἶ (“You are truly the Son of God”) – Jesus’ disciples had the correct and highest evaluation of Jesus.

Matthew 27:40, εἰ υἱὸς εἶ τοῦ θεοῦ (“If you are the Son of God”) – The mockers are mocking Jesus with his own words. It would not make sense to tease him with being “a” son of God. But is this the concept the Roman soldier repeated when he became aware of Jesus’ uniqueness (27:54)?

Mark 12:28, ποία ἐστὶν ἐντολὴ πρώτη πάντων (“which is the first commandment of all”) – definite only possibility because of πρώτη

Luke 1:36, οὗτος μὴν ἕκτος ἐστὶν (“this is the sixth month”) – There is only one sixth month.

Luke 1:63, Ἰωάννης ἐστὶν ὄνομα αὐτοῦ (“the name of him is John” or “John is the name of him”) – The only question is whether John is the subject or the predicate nominative

Luke 4:3, εἰ υἱὸς εἶ τοῦ θεοῦ (“If you are the Son of God”) – It would not make sense for Satan to challenge Jesus with being “a” son of God.

Luke 4:9, εἰ υἱὸς εἶ τοῦ θεοῦ (“If you are the Son of God”) – It would not make sense for Satan to challenge Jesus with being “a” son of God.

John 1:49, σὺ βασιλεὺς εἶ τοῦ Ἰσραήλ (“you are the king of Israel”) – It would not be much of a declaration by Jesus’ disciple that Jesus is a king of Israel.

John 3:29, ὁ ἔχων τὴν νύμφην νυμφίος ἐστίν (“the one who has the bride is the bridegroom”)

John 8:42, εἰ ὁ θεὸς πατὴρ ὑμῶν ἦν (“if God was the father of you”) – He is not “a” father of us

John 8:54, ὃν ὑμεῖς λέγετε ὅτι θεὸς ἡμῶν ἐστιν (“whom you say that he is the God of you”) – Jesus wasn’t accusing the Jews of making God only one of many.

John 9:5, φῶς εἰμι τοῦ κόσμου (“I am the light of the world”)

John 9:37, ὁ λαλῶν μετὰ σοῦ ἐκεῖνός ἐστιν (“the one speaking to you is that one”) – The pronoun makes for a definite sense.

John 10:2, ὁ δὲ εἰσερχόμενος διὰ τῆς θύρας ποιμήν ἐστιν τῶν προβάτων (“the one who enters through the door is the shepherd of the sheep”)– Jesus’ point in context is that he is that definite and only shepherd

John 10:36, ὅτι εἶπον· υἱὸς τοῦ θεοῦ εἰμι (“because I said, ‘I am the Son of God”) – There is a bit of theological wrangling going on in this exchange but it does not seem likely that Jesus is backing down his self-evaluation to “a” son of God to escape the charge of blasphemy.

John 11:49, ἀρχιερεὺς ὢν τοῦ ἐνιαυτοῦ ἐκείνου (“being the high priest that year”) – There is only one high priest.

John 11:51, ἀρχιερεὺς ὢν τοῦ ἐνιαυτοῦ ἐκείνου ἐπροφήτευσεν (“being the high priest that year, he prophesied”)

Acts 19:35, τὴν Ἐφεσίων πόλιν νεωκόρον οὖσαν (“the city of Ephesus is the temple-keeper”) – It must be “the” city since it is further identified as Ephesus.

Romans 1:16, τὸ εὐαγγέλιον, δύναμις γὰρ θεοῦ ἐστιν (“the gospel, for it is the power of God”) – The gospel is not “a” power of God to salvation but “the” power.

1 Corinthians 1:18, δύναμις θεοῦ ἐστιν (“It is the power of God”) – The gospel, the word of the cross, is “the” power of God to those being saved.

1 Corinthians 4:4, ὁ δὲ ἀνακρίνων με κύριός ἐστιν (“the one who judges me is the Lord”) – not “a” lord

1 Corinthians 11:7a, δόξα θεοῦ ὑπάρχων (“being the image of God”) – only one image of God

1 Corinthians 11:7b, ἡ γυνὴ δὲ δόξα ἀνδρός ἐστιν (“and the wife is the glory of the husband”) – not “a” husband”

Philippians 2:13, θεὸς γάρ ἐστιν (“for it is God”) – There is only one God

1 John 2:18a, ἐσχάτη ὥρα ἐστίν (“it is the last hour”) – definite only possibility because of ἐσχάτη

Revelation 1:20, οἱ ἑπτὰ ἀστέρες ἄγγελοι τῶν ἑπτὰ ἐκκλησιῶν εἰσιν καὶ αἱ λυχνίαι αἱ ἑπτὰ ἑπτὰ ἐκκλησίαι εἰσίν (“the seven stars are the angels of the seven churches and the seven lampstands are the churches”) – Jesus is making identifications, making definite the meaning of symbols

Revelation 21:22, ὁ γὰρ κύριος ὁ θεὸς ὁ παντοκράτωρ ναὸς αὐτῆς ἐστιν καὶ τὸ ἀρνίον (“For the Lord God Almighty is the temple, and the Lamb”) – God and the Lamb are the only temple of the New Jerusalem

=31 instances.

We expect this with Colwell’s Rule, but not with the same frequency as those following the verb.

Those exceptions seem to disprove the rule.

Anarthrous Predicate Nominatives preceding the verb where a qualitative interpretation seems

the most likely possibility:

Matthew 23:8b, πάντες δὲ ὑμεῖς ἀδελφοί ἐστε (“You are all brothers”) – All Jesus’ disciples share the same quality, they are brothers/sisters. They are not all “the” rothers.

Matthew 27:6, τιμὴ αἵματός ἐστιν (“It is money of blood”) – It is the kind of money that cannot be allowed in the temple treasury.

Mark 12:29, κύριος εἷς ἐστιν (“the Lord is one”) – not “a” one or “the” one but the quality of oneness

Luke 14:22, ἔτι τόπος ἐστίν (“there is still room”) – The servants are not concerned that there is still “a” room available for the wedding, but the quality of room, space available still at the banquet.

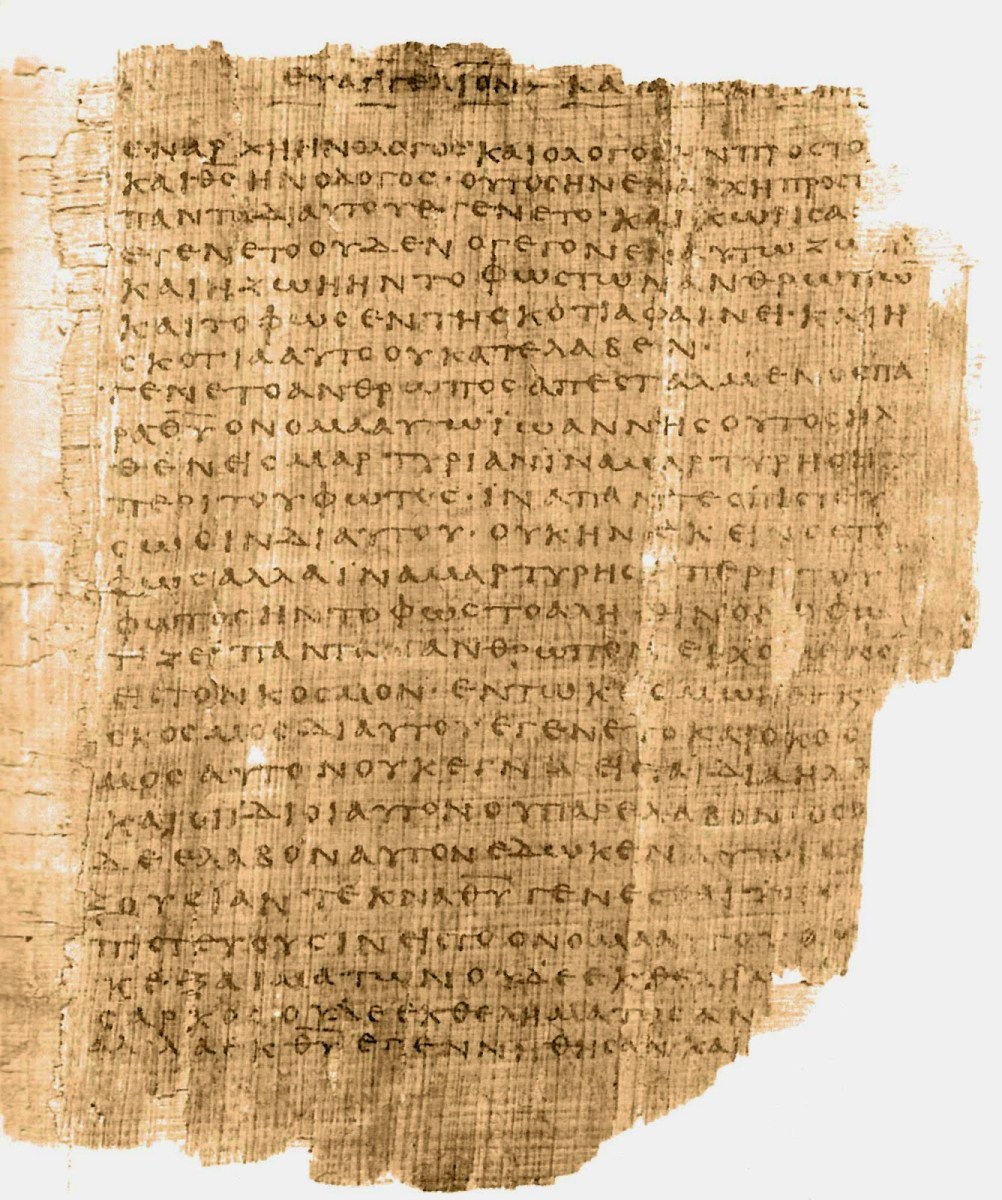

John 1:14, ὁ λόγος σὰρξ ἐγένετο (“The Word became flesh”) – Jesus did not become “a” or “the” flesh, but flesh as an element.

John 2:9, τὸ ὕδωρ οἶνον γεγενημένον [pred acc or d/o] (“the water had become wine”) – not “a” or “the” wine but wine as a substance

John 3:4, ἄνθρωπος γεννηθῆναι γέρων ὤν (“a man to be born, when he is old”) – Γέρων is a noun, not an adjective, but the qualitative predicate nominative can act like an adjective

John 3:6, τὸ γεγεννημένον ἐκ τῆς σαρκὸς σάρξ ἐστιν, καὶ τὸ γεγεννημένον ἐκ τοῦ πνεύματος πνεῦμά ἐστιν (“that which is born of the flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit”) – neither “a” nor “the” work

John 6:63b, τὰ ῥήματα ἃ ἐγὼ λελάληκα ὑμῖν πνεῦμά ἐστιν καὶ ζωή ἐστιν (“the words that I speak are spirit and life”) – neither “a” nor “the” work

John 9:4, ἕως ἡμέρα ἐστίν (“while it is day”)

John 10:22, χειμὼν ἦν (“it was winter”)

John 12:50, ἡ ἐντολὴ αὐτοῦ ζωὴ αἰώνιός ἐστιν (“His command is eternal life”)

John 17:17, ὁ λόγος ὁ σὸς ἀλήθειά ἐστιν (“Your word is truth”)

John 20:1, σκοτίας ἔτι οὔσης (“while it was still dark”)

Acts 7:33, τόπος ἐφ’ ᾧ ἕστηκας γῆ ἁγία ἐστίν (“the place on which you stand is holy

ground”)

most likely possibility:

Matthew 5:34, θρόνος ἐστὶν τοῦ θεοῦ (“it is the throne of God”) – There is only one throne of God.

Matthew 5:35, μήτε εἰς Ἱεροσόλυμα, ὅτι πόλις ἐστὶν τοῦ μεγάλου βασιλέως (“nor by Jerusalem, because it is the city of the Great King”) – There is only one Jerusalem, one city of the great King.

Matthew 12:50, αὐτός μου ἀδελφὸς καὶ ἀδελφὴ καὶ μήτηρ ἐστίν (“he is the brother of me and the sister of me and the mother of me”) – By comparison with v.48 where brother, sister and mother have the article, it is evident that these terms are definite here as well.

Matthew 13:39b, ὁ δὲ θερισμὸς συντέλεια αἰῶνός ἐστιν (“and the harvest is the end of the age”)

Matthew 14:33, ἀληθῶς θεοῦ υἱὸς εἶ (“You are truly the Son of God”) – Jesus’ disciples had the correct and highest evaluation of Jesus.

Matthew 27:40, εἰ υἱὸς εἶ τοῦ θεοῦ (“If you are the Son of God”) – The mockers are mocking Jesus with his own words. It would not make sense to tease him with being “a” son of God. But is this the concept the Roman soldier repeated when he became aware of Jesus’ uniqueness (27:54)?

Mark 12:28, ποία ἐστὶν ἐντολὴ πρώτη πάντων (“which is the first commandment of all”) – definite only possibility because of πρώτη

Luke 1:36, οὗτος μὴν ἕκτος ἐστὶν (“this is the sixth month”) – There is only one sixth month.

Luke 1:63, Ἰωάννης ἐστὶν ὄνομα αὐτοῦ (“the name of him is John” or “John is the name of him”) – The only question is whether John is the subject or the predicate nominative

Luke 4:3, εἰ υἱὸς εἶ τοῦ θεοῦ (“If you are the Son of God”) – It would not make sense for Satan to challenge Jesus with being “a” son of God.

Luke 4:9, εἰ υἱὸς εἶ τοῦ θεοῦ (“If you are the Son of God”) – It would not make sense for Satan to challenge Jesus with being “a” son of God.

John 1:49, σὺ βασιλεὺς εἶ τοῦ Ἰσραήλ (“you are the king of Israel”) – It would not be much of a declaration by Jesus’ disciple that Jesus is a king of Israel.

John 3:29, ὁ ἔχων τὴν νύμφην νυμφίος ἐστίν (“the one who has the bride is the bridegroom”)

John 8:42, εἰ ὁ θεὸς πατὴρ ὑμῶν ἦν (“if God was the father of you”) – He is not “a” father of us

John 8:54, ὃν ὑμεῖς λέγετε ὅτι θεὸς ἡμῶν ἐστιν (“whom you say that he is the God of you”) – Jesus wasn’t accusing the Jews of making God only one of many.

John 9:5, φῶς εἰμι τοῦ κόσμου (“I am the light of the world”)

John 9:37, ὁ λαλῶν μετὰ σοῦ ἐκεῖνός ἐστιν (“the one speaking to you is that one”) – The pronoun makes for a definite sense.

John 10:2, ὁ δὲ εἰσερχόμενος διὰ τῆς θύρας ποιμήν ἐστιν τῶν προβάτων (“the one who enters through the door is the shepherd of the sheep”)– Jesus’ point in context is that he is that definite and only shepherd

John 10:36, ὅτι εἶπον· υἱὸς τοῦ θεοῦ εἰμι (“because I said, ‘I am the Son of God”) – There is a bit of theological wrangling going on in this exchange but it does not seem likely that Jesus is backing down his self-evaluation to “a” son of God to escape the charge of blasphemy.

John 11:49, ἀρχιερεὺς ὢν τοῦ ἐνιαυτοῦ ἐκείνου (“being the high priest that year”) – There is only one high priest.

John 11:51, ἀρχιερεὺς ὢν τοῦ ἐνιαυτοῦ ἐκείνου ἐπροφήτευσεν (“being the high priest that year, he prophesied”)

Acts 19:35, τὴν Ἐφεσίων πόλιν νεωκόρον οὖσαν (“the city of Ephesus is the temple-keeper”) – It must be “the” city since it is further identified as Ephesus.

Romans 1:16, τὸ εὐαγγέλιον, δύναμις γὰρ θεοῦ ἐστιν (“the gospel, for it is the power of God”) – The gospel is not “a” power of God to salvation but “the” power.

1 Corinthians 1:18, δύναμις θεοῦ ἐστιν (“It is the power of God”) – The gospel, the word of the cross, is “the” power of God to those being saved.

1 Corinthians 4:4, ὁ δὲ ἀνακρίνων με κύριός ἐστιν (“the one who judges me is the Lord”) – not “a” lord

1 Corinthians 11:7a, δόξα θεοῦ ὑπάρχων (“being the image of God”) – only one image of God

1 Corinthians 11:7b, ἡ γυνὴ δὲ δόξα ἀνδρός ἐστιν (“and the wife is the glory of the husband”) – not “a” husband”

Philippians 2:13, θεὸς γάρ ἐστιν (“for it is God”) – There is only one God

1 John 2:18a, ἐσχάτη ὥρα ἐστίν (“it is the last hour”) – definite only possibility because of ἐσχάτη

Revelation 1:20, οἱ ἑπτὰ ἀστέρες ἄγγελοι τῶν ἑπτὰ ἐκκλησιῶν εἰσιν καὶ αἱ λυχνίαι αἱ ἑπτὰ ἑπτὰ ἐκκλησίαι εἰσίν (“the seven stars are the angels of the seven churches and the seven lampstands are the churches”) – Jesus is making identifications, making definite the meaning of symbols

Revelation 21:22, ὁ γὰρ κύριος ὁ θεὸς ὁ παντοκράτωρ ναὸς αὐτῆς ἐστιν καὶ τὸ ἀρνίον (“For the Lord God Almighty is the temple, and the Lamb”) – God and the Lamb are the only temple of the New Jerusalem

=31 instances.

We expect this with Colwell’s Rule, but not with the same frequency as those following the verb.

Those exceptions seem to disprove the rule.

Anarthrous Predicate Nominatives preceding the verb where a qualitative interpretation seems

the most likely possibility:

Matthew 23:8b, πάντες δὲ ὑμεῖς ἀδελφοί ἐστε (“You are all brothers”) – All Jesus’ disciples share the same quality, they are brothers/sisters. They are not all “the” rothers.

Matthew 27:6, τιμὴ αἵματός ἐστιν (“It is money of blood”) – It is the kind of money that cannot be allowed in the temple treasury.

Mark 12:29, κύριος εἷς ἐστιν (“the Lord is one”) – not “a” one or “the” one but the quality of oneness

Luke 14:22, ἔτι τόπος ἐστίν (“there is still room”) – The servants are not concerned that there is still “a” room available for the wedding, but the quality of room, space available still at the banquet.

John 1:14, ὁ λόγος σὰρξ ἐγένετο (“The Word became flesh”) – Jesus did not become “a” or “the” flesh, but flesh as an element.

John 2:9, τὸ ὕδωρ οἶνον γεγενημένον [pred acc or d/o] (“the water had become wine”) – not “a” or “the” wine but wine as a substance

John 3:4, ἄνθρωπος γεννηθῆναι γέρων ὤν (“a man to be born, when he is old”) – Γέρων is a noun, not an adjective, but the qualitative predicate nominative can act like an adjective

John 3:6, τὸ γεγεννημένον ἐκ τῆς σαρκὸς σάρξ ἐστιν, καὶ τὸ γεγεννημένον ἐκ τοῦ πνεύματος πνεῦμά ἐστιν (“that which is born of the flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit”) – neither “a” nor “the” work

John 6:63b, τὰ ῥήματα ἃ ἐγὼ λελάληκα ὑμῖν πνεῦμά ἐστιν καὶ ζωή ἐστιν (“the words that I speak are spirit and life”) – neither “a” nor “the” work

John 9:4, ἕως ἡμέρα ἐστίν (“while it is day”)

John 10:22, χειμὼν ἦν (“it was winter”)

John 12:50, ἡ ἐντολὴ αὐτοῦ ζωὴ αἰώνιός ἐστιν (“His command is eternal life”)

John 17:17, ὁ λόγος ὁ σὸς ἀλήθειά ἐστιν (“Your word is truth”)

John 20:1, σκοτίας ἔτι οὔσης (“while it was still dark”)

Acts 7:33, τόπος ἐφ’ ᾧ ἕστηκας γῆ ἁγία ἐστίν (“the place on which you stand is holy

ground”)